About Cerro del Villar

Founded in around 760 BC, Cerro del Villar is one of the most important Phoenician settlements in the western Mediterranean, thriving for almost 200 years until it was peacefully abandoned, with the population probably moving four kilometres west to Malaka (modern-day Malaga).

Originally located on a small island just five metres above sea level, Cerro del Villar was vulnerable to flooding due to its marshy conditions and deforestation, but its position at the mouth of the largest river in Andalucia with one of the best harbours on the coast was strategic, controlling trade between the Mediterranean and southern Spain’s fertile interior.

The prosperity of Cerro del Villar is evident from the settlement's expansion to cover the entire island and its lack of fortifications, suggesting friendly relations with the local population and status as a neutral meeting space for traders and cultural exchange.

The Cerro del Villar archaeological site was first excavated in 1966, with further work from 1986 led by the esteemed Maria Eugenia Aubet (ongoing under José Suárez Padilla) confirming that the Phoenician settlement was the economic hub of Spain’s southern coast almost 3,000 years ago.

The Guadalhorce waterway gave the Phoenician settlers access to the rich agricultural resources of the Guadalhorce valley and its local communities, while the settlement’s port facilities could handle the cargo of both large ships and smaller river boats.

Cerro del Villar also offered an overland route to the heartland and mineral reserves of Tartessos, and was one of the last safe harbours before the challenging crossing of the Straits of Gibraltar through the Pillars of Hercules en route to Cadiz.

Although only a small proportion of the site has been excavated, clear signs of its sophisticated urban layout have emerged, including large brick residences surrounded by a network of streets, covered walkways and open spaces. Some of these luxurious dwellings were at least two storeys high, with six or more rooms arranged around an interior courtyard and direct access to the sea via private jetties.

Evidence of Cerro del Villar’s thriving economy comes from the site’s marketplace, port infrastructure and industrial zone. The settlement was the regional centre for commercial wheel-made pottery production, particularly tableware, which was a revolutionary upgrade on local handmade ceramics and highly prized by indigenous communities.

Apart from ceramics manufacturing, the site's industrial area included workshops for processing metals like iron, bronze, copper, lead and silver, and facilities for the production of coloured textiles (large quantities of murex shells used to produce Tyrian purple dye were found in one building). Cerro del Villar’s status and role in Mediterranean trade is also clear from the Greek and Etruscan pottery found at the site, as well as imports from the Phoenician sister settlement of Carthage in North Africa.

Another advantage of Cerro del Villar was its fertile river valley with 18 km² of land remarkably well suited to intensive and high-yield agriculture. Wheat, barley, oats, lentils, grapes and peaches were grown, with the number of stone mills for grinding corn discovered indicating that the limited population of the Phoenician settlement must have produced a surplus of grain for export.

While wine was imported from the east in Cerro del Villar’s early days, vineyards soon sprang up around the settlement, and ceramic transport and storage containers (amphorae) containing grape residue found in the industrial zone suggest that previously uncultivated alcoholic wine was unsurprisingly popular with local customers.

The discovery of abundant remains of cattle, sheep, goats and fish, as well as equipment including hooks, lead weights and harpoons shows that the inhabitants practiced stockrearing, animal husbandry and commercial fishing. The remains of meat and tuna inside amphorae also point to preserved foods being a popular export, with expensive fermented fish sauce (garum) probably produced in quantity soon after the settlement’s foundation.

The site of Cerro del Villar’s necropolis is disputed. Cortijo de San Isidro in La Rebanadilla is nearby, but its late ninth century BC burials mean that it appears to have been used before the settlement was founded. A number of Phoenican alabaster urns containing cremated remains have been found in shaft tombs at Cortijo de Montañez which is also close to the site, as is the mainly Punic cemetery at Jardin, but no main necropolis reflecting the status, duration and diversity of Cerro del Villar has so far been discovered.

Phoenician Red Slip Ware

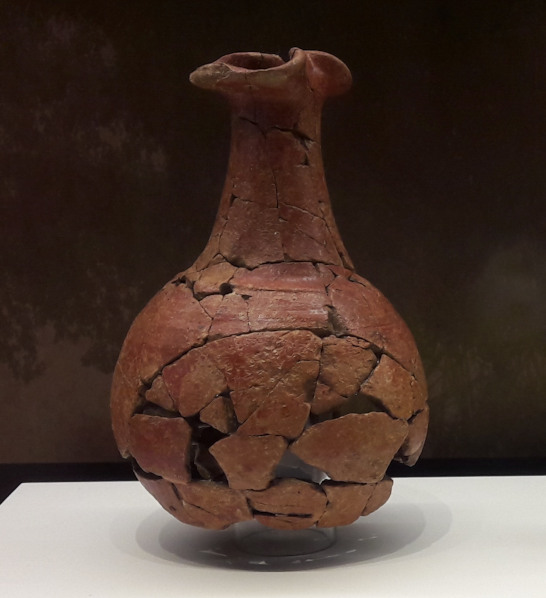

Phoenician 'red slip' refers to a coating of red clay that was applied to a vessel’s golden-coloured surface, and then polished and smoothed. Originally produced in the Phoenician homeland and later in the western Mediterranean settlements, red slip ware was considered a status symbol due to the high sheen and reddish-brown finish that was intended to resemble bronze.

Apart from plates, bowls and saucers, common Phoenician tableware included 'mushroom-mouth' jugs with wide rims and 'trefoil-mouth' jugs with three spouts shaped like flower petals. Both were used in domestic settings, during funerals and at feasts, where the distinctive design of the trefoil jug enabled the controlled pouring of wine in three directions at a crowded table.

The presence of red slip tableware is a key footprint of the Phoenicians, either as traders or settlers, and is found at sites across the Mediterranean. The differing width of red slip plate rims has also been crucial in allowing archaeologists to establish a timeline for the early Phoenician presence in southern Spain.

Address

Opening Hours

Tues-Sat: 9am–9pm

Sun & holidays: 9am–3pm

Mon: Closed

Free admission for EU citizens and Spanish residents. Other visitors: €1.50.

The Museum of Malaga is located in the Palacio de la Aduana (Customs Palace) next to the hill of the Alcazaba in the centre of the city. The imposing neoclassical building was built in 1791 and became Malaga’s main museum in 1973, before undergoing refurbishment from 2008 until its reopening in 2016.

The museum brings together the collections of the former Provincial Museum of Fine Arts and the Provincial Archaeological Museum, and is divided into two sections, with more than 2,000 fine arts pieces and 15,000 in the archaeology collection making it the largest museum in Andalucia and the fifth largest in Spain.

One room is dedicated to the discoveries made since 1964 at the Phoenician sites of Toscanos, Trayamar, Morro de Mezquitilla, Jardín and Chorreras by the German Archaeological Institute. Highlights include the Trayamar Medallion (pictured), a shaft tomb from Chorreras, artefacts from Cerro del Villar, and the mysterious ‘Tomb of the Warrior’.